1.8: Internet Backbones, NAPs, and ISPs

| Our discussion

of layering in the previous section has perhaps given the impression that

the Internet is a carefully organized and highly intertwined structure.

This is certainly true in the sense that all of the network entities (end

systems, routers, and bridges) use a common set of protocols, enabling

the entities to communicate with each other. However, from a topological

perspective, to many people the Internet seems to be growing in a chaotic

manner, with new sections, branches, and wings popping up in random places

on a daily basis. Indeed, unlike the protocols, the Internet's topology

can grow and evolve without approval from a central authority. Let us now

try to get a grip on the seemingly nebulous Internet topology.

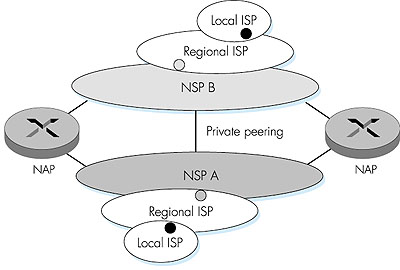

As we mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, the topology of the Internet is loosely hierarchical. Roughly speaking, from bottom-to-top the hierarchy consists of end systems (PCs, workstations, and so on) connected to local Internet service providers (ISPs). The local ISPs are in turn connected to regional ISPs, which are in turn connected to national and international ISPs. The national and international ISPs are connected together at the highest tier in the hierarchy. New tiers and branches can be added just as a new piece of Lego can be attached to an existing Lego construction. In this section we describe the topology of the Internet in the United States as of 2000. Let's begin at the top of the hierarchy and work our way down. Residing at the very top of the hierarchy are the national ISPs, which are called national service providers (NSPs). The NSPs form independent backbone networks that span North America (and typically extend abroad as well). Just as there are multiple long-distance telephone companies in the United States, there are multiple NSPs that compete with each other for traffic and customers. The existing NSPs include internetMCI, SprintLink, PSINet, UUNet Technologies, and AGIS. The NSPs typically have high-bandwidth transmission links, with bandwidths ranging from 1.5 Mbps to 622 Mbps and higher. Each NSP also has numerous hubs that interconnect its links and at which regional ISPs can tap into the NSP. The NSPs themselves must be interconnected to each other. To see this, suppose one regional ISP, say MidWestnet, is connected to the MCI NSP and another regional ISP, say EastCoastnet, is connected to Sprint's NSP. How can traffic be sent from MidWestnet to EastCoastnet? The solution is to introduce switching centers, called network access points (NAPs), which interconnect the NSPs, thereby allowing each regional ISP to pass traffic to any other regional ISP. To keep us all confused, some of the NAPs are not referred to as NAPs but instead as MAEs (metropolitan area exchanges). In the United States, many of the NAPs are run by RBOCs (regional Bell operating companies); for example, PacBell has a NAP in San Francisco and Ameritech has a NAP in Chicago. For a list of major NSPs (those connected into at least three MAPs/MAE's), see [Haynal 1999]. In addition to connecting to each other at NAPs, NSPs can connect to each other through so-called private peering points; see Figure 1.26. For a discussion of NAPs as well as private peering among NSPs, see [Huston 1999a].

Because the NAPs relay and switch tremendous volumes of Internet traffic, they are typically in themselves complex high-speed switching networks concentrated in a small geographical area (for example, a single building). Often the NAPs use high-speed ATM switching technology in the heart of the NAP, with IP riding on top of ATM. Figure 1.27 illustrates PacBell's San Francisco NAP. The details of Figure 1.27 are unimportant for us now; it is worthwhile to note, however, that the NSP hubs can themselves be complex data networks.

Running an NSP is not cheap. In June 1996, the cost of leasing 45 Mbps fiber optics from coast to coast, as well as the additional hardware required, was approximately $150,000 per month. And the fees that an NSP pays the NAPs to connect to the NAPs can exceed $300,000 annually. NSPs and NAPs also have significant capital costs in equipment for high-speed networking. An NSP earns money by charging a monthly fee to the regional ISPs that connect to it. The fee that an NSP charges to a regional ISP typically depends on the bandwidth of the connection between the regional ISP and the NSP; clearly a 1.5 Mbps connection would be charged less than a 45 Mbps connection. Once the fixed-bandwidth connection is in place, the regional ISP can pump and receive as much data as it pleases, up to the bandwidth of the connection, at no additional cost. If an NSP has significant revenues from the regional ISPs that connect to it, it may be able to cover the high capital and monthly costs of setting up and maintaining an NSP. For a discussion of the current practice of financial settlement among interconnected network providers, see [Huston 1999b]. A regional ISP is also a complex network, consisting of routers and transmission links with rates ranging from 64 Kbps upward. A regional ISP typically taps into an NSP (at an NSP hub), but it can also tap directly into a NAP, in which case the regional ISP pays a monthly fee to a NAP instead of to an NSP. A regional ISP can also tap into the Internet backbone at two or more distinct points (for example, at an NSP hub or at a NAP). How does a regional ISP cover its costs? To answer this question, let's jump to the bottom of the hierarchy. End systems gain access to the Internet by connecting to a local ISP. Universities and corporations can act as local ISPs, but backbone service providers can also serve as a local ISP. Many local ISPs are small "mom and pop" companies, however. A popular Web site known simply as "The List" contains links to nearly 8,000 local, regional, and backbone ISPs [List 1999]. The local ISPs tap into one of the regional ISPs in its region. Analogous to the fee structure between the regional ISP and the NSP, the local ISP pays a monthly fee to its regional ISP that depends on the bandwidth of the connection. Finally, the local ISP charges its customers (typically) a flat, monthly fee for Internet access: the higher the transmission rate of the connection, the higher the monthly fee. We conclude this section by mentioning that any one of us can become a local ISP as soon as we have an Internet connection. All we need to do is purchase the necessary equipment (for example, router and modem pool) that is needed to allow other users to connect to our so-called point of presence. Thus, new tiers and branches can be added to the Internet topology just as a new piece of Lego can be attached to an existing Lego construction. |