2.2: The World Wide Web: HTTP

| Until the 1990s

the Internet was used primarily by researchers, academics, and university

students to log-in to remote hosts, to transfer files from local hosts

to remote hosts and vice versa, to receive and send news, and to receive

and send electronic mail. Although these applications were (and continue

to be) extremely useful, the Internet was essentially unknown outside the

academic and research communities. Then, in the early 1990s, the Internet's

killer application arrived on the scene--the World Wide Web [Berners-Lee

1994]. The Web is the Internet application that caught the general

public's eye. It is dramatically changing how people interact inside and

outside their work environments. It has spawned thousands of start up companies.

It has elevated the Internet from just one of many data networks (including

online networks such as Prodigy, America OnLine, and Compuserve, national

data networks such as Minitel/Transpac in France, private X.25, and frame

relay networks) to essentially the one and only data network.

History is sprinkled with the arrival of electronic communication technologies that have had major societal impacts. The first such technology was the telephone, invented in the 1870s. The telephone allowed two persons to orally communicate in real-time without being in the same physical location. It had a major impact on society--both good and bad. The next electronic communication technology was broadcast radio/television, which arrived in the 1920s and 1930s. Broadcast radio/ television allowed people to receive vast quantities of audio and video information. It also had a major impact on society--both good and bad. The third major communication technology that has changed the way people live and work is the Web. Perhaps what appeals the most to users about the Web is that it operates on demand. Users receive what they want, when they want it. This is unlike broadcast radio and television, which force users to "tune in" when the content provider makes the content available. In addition to being on demand, the Web has many other wonderful features that people love and cherish. It is enormously easy for any individual to make any information available over the Web; everyone can become a publisher at extremely low cost. Hyperlinks and search engines help us navigate through an ocean of Web sites. Graphics and animated graphics stimulate our senses. Forms, Java applets, Active X components, as well as many other devices enable us to interact with pages and sites. And more and more, the Web provides a menu interface to vast quantities of audio and video material stored in the Internet, audio and video that can be accessed on demand.

2.2.1: Overview of HTTPThe Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), the Web's application-layer protocol, is at the heart of the Web. HTTP is implemented in two programs: a client program and a server program. The client program and server program, executing on different end systems, talk to each other by exchanging HTTP messages. HTTP defines the structure of these messages and how the client and server exchange the messages. Before explaining HTTP in detail, it is useful to review some Web terminology.A Web page (also called a document) consists of objects. An object is simply a file--such as an HTML file, a JPEG image, a GIF image, a Java applet, an audio clip, and so on--that is addressable by a single URL. Most Web pages consist of a base HTML file and several referenced objects. For example, if a Web page contains HTML text and five JPEG images, then the Web page has six objects: the base HTML file plus the five images. The base HTML file references the other objects in the page with the objects' URLs. Each URL has two components: the host name of the server that houses the object and the object's path name. For example, the URL www.someSchool.edu/someDepartment/picture.gif has www.someSchool.edu for a host name and /someDepartment/picture.gif for a path name. A browser is a user agent for the Web; it displays the requested Web page and provides numerous navigational and configuration features. Web browsers also implement the client side of HTTP. Thus, in the context of the Web, we will interchangeably use the words "browser" and "client." Popular Web browsers include Netscape Communicator and Microsoft Internet Explorer. A Web server houses Web objects, each addressable by a URL. Web servers also implement the server side of HTTP. Popular Web servers include Apache, Microsoft Internet Information Server, and the Netscape Enterprise Server. (Netcraft provides a nice survey of Web server penetration [Netcraft 2000].) HTTP defines how Web clients (that is, browsers) request Web pages from servers (that is, Web servers) and how servers transfer Web pages to clients. We discuss the interaction between client and server in detail below, but the general idea is illustrated in Figure 2.6. When a user requests a Web page (for example, clicks on a hyperlink), the browser sends HTTP request messages for the objects in the page to the server. The server receives the requests and responds with HTTP response messages that contain the objects. Through 1997 essentially all browsers and Web servers implemented version HTTP/1.0, which is defined in RFC 1945. Beginning in 1998, some Web servers and browsers began to implement version HTTP/1.1, which is defined in RFC 2616. HTTP/1.1 is backward compatible with HTTP/1.0; a Web server running 1.1 can "talk" with a browser running 1.0, and a browser running 1.1 can "talk" with a server running 1.0.

Both HTTP/1.0 and HTTP/1.1 use TCP as their underlying transport protocol (rather than running on top of UDP). The HTTP client first initiates a TCP connection with the server. Once the connection is established, the browser and the server processes access TCP through their socket interfaces. As described in Section 2.1, on the client side the socket interface is the "door" between the client process and the TCP connection; on the server side it is the "door" between the server process and the TCP connection. The client sends HTTP request messages into its socket interface and receives HTTP response messages from its socket interface. Similarly, the HTTP server receives request messages from its socket interface and sends response messages into the socket interface. Once the client sends a message into its socket interface, the message is "out of the client's hands" and is "in the hands of TCP." Recall from Section 2.1 that TCP provides a reliable data transfer service to HTTP. This implies that each HTTP request message emitted by a client process eventually arrives intact at the server; similarly, each HTTP response message emitted by the server process eventually arrives intact at the client. Here we see one of the great advantages of a layered architecture--HTTP need not worry about lost data, or the details of how TCP recovers from loss or reordering of data within the network. That is the job of TCP and the protocols in the lower layers of the protocol stack. TCP also employs a congestion control mechanism that we shall discuss in detail in Chapter 3. We mention here only that this mechanism forces each new TCP connection to initially transmit data at a relatively slow rate, but then allows each connection to ramp up to a relatively high rate when the network is uncongested. The initial slow-transmission phase is referred to as slow start. It is important to note that the server sends requested files to clients without storing any state information about the client. If a particular client asks for the same object twice in a period of a few seconds, the server does not respond by saying that it just served the object to the client; instead, the server resends the object, as it has completely forgotten what it did earlier. Because an HTTP server maintains no information about the clients, HTTP is said to be a stateless protocol. 2.2.2: Nonpersistent and Persistent ConnectionsHTTP can use both nonpersistent connections and persistent connections. HTTP/ 1.0 uses nonpersistent connections. Conversely, use of persistent connections is the default mode for HTTP/1.1.Nonpersistent Connections Let us walk through the steps of transferring a Web page from server to client for the case of nonpersistent connections. Suppose the page consists of a base HTML file and 10 JPEG images, and that all 11 of these objects reside on the same server. Suppose the URL for the base HTML file is www.someSchool.edu/someDepartment/home.index. Here is what happens:

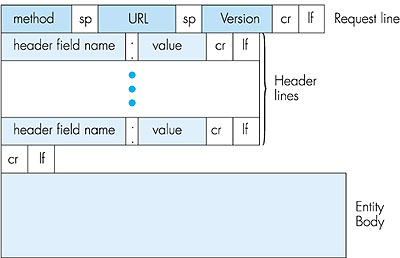

The steps above use nonpersistent connections because each TCP connection is closed after the server sends the object--the connection does not persist for other objects. Note that each TCP connection transports exactly one request message and one response message. Thus, in this example, when a user requests the Web page, 11 TCP connections are generated. In the steps described above, we were intentionally vague about whether the client obtains the 10 JPEGs over 10 serial TCP connections, or whether some of the JPEGs are obtained over parallel TCP connections. Indeed, users can configure modern browsers to control the degree of parallelism. In their default modes, most browsers open 5 to 10 parallel TCP connections, and each of these connections handles one request-response transaction. If the user prefers, the maximum number of parallel connections can be set to 1, in which case the 10 connections are established serially. As we shall see in the next chapter, the use of parallel connections shortens the response time. Before continuing, let's do a back-of-the-envelope calculation to estimate the amount of time from a client requesting the base HTML file until the file is received by the client. To this end we define the round-trip time (RTT), which is the time it takes for a small packet to travel from client to server and then back to the client. The RTT includes packet-propagation delays, packet-queuing delays in intermediate routers and switches, and packet-processing delays. (These delays were discussed in Section 1.6.) Now consider what happens when a user clicks on a hyperlink. This causes the browser to initiate a TCP connection between the browser and the Web server; this involves a "three-way handshake"--the client sends a small TCP message to the server, the server acknowledges and responds with a small message, and, finally, the client acknowledges back to the server. One RTT elapses after the first two parts of the three-way handshake. After completing the first two parts of the handshake, the client sends the HTTP request message into the TCP connection, and TCP "piggybacks" the last acknowledgment (the third part of the three-way handshake) onto the request message. Once the request message arrives at the server, the server sends the HTML file into the TCP connection. This HTTP request/response eats up another RTT. Thus, roughly, the total response time is two RTTs plus the transmission time at the server of the HTML file. Persistent Connections Nonpersistent connections have some shortcomings. First, a brand new connection must be established and maintained for each requested object. For each of these connections, TCP buffers must be allocated and TCP variables must be kept in both the client and server. This can place a serious burden on the Web server, which may be serving requests from hundreds of different clients simultaneously. Second, as we just described, each object suffers two RTTs--one RTT to establish the TCP connection and one RTT to request and receive an object. Finally, each object suffers from TCP slow start because every TCP connection begins with a TCP slow-start phase. The impact of RTT and slow-start delays can be partially mitigated, however, by the use of parallel TCP connections. With persistent connections, the server leaves the TCP connection open after sending a response. Subsequent requests and responses between the same client and server can be sent over the same connection. In particular, an entire Web page (in the example above, the base HTML file and the 10 images) can be sent over a single persistent TCP connection; moreover, multiple Web pages residing on the same server can be sent over a single persistent TCP connection. Typically, the HTTP server closes a connection when it isn't used for a certain time (the timeout interval), which is often configurable. There are two versions of persistent connections: without pipelining and with pipelining. For the version without pipelining, the client issues a new request only when the previous response has been received. In this case, each of the referenced objects (the 10 images in the example above) experiences one RTT in order to request and receive the object. Although this is an improvement over nonpersistent's two RTTs, the RTT delay can be further reduced with pipelining. Another disadvantage of no pipelining is that after the server sends an object over the persistent TCP connection, the connection hangs--does nothing--while it waits for another request to arrive. This hanging wastes server resources. The default mode of HTTP/1.1 uses persistent connections with pipelining. In this case, the HTTP client issues a request as soon as it encounters a reference. Thus the HTTP client can make back-to-back requests for the referenced objects. When the server receives the requests, it can send the objects back to back. If all the requests are sent back to back and all the responses are sent back to back, then only one RTT is expended for all the referenced objects (rather than one RTT per referenced object when pipelining isn't used). Furthermore, the pipelined TCP connection hangs for a smaller fraction of time. In addition to reducing RTT delays, persistent connections (with or without pipelining) have a smaller slow-start delay than nonpersistent connections. The reason is that after sending the first object, the persistent server does not have to send the next object at the initial slow rate since it continues to use the same TCP connection. Instead, the server can pick up at the rate where the first object left off. We shall quantitatively compare the performance of nonpersistent and persistent connections in the homework problems of Chapter 3. The interested reader is also encouraged to see [Heidemann 1997; Nielsen 1997]. 2.2.3: HTTP Message FormatThe HTTP specifications 1.0 ([RFC 1945] and 1.1 [RFC 2616]) define the HTTP message formats. There are two types of HTTP messages, request messages and response messages, both of which are discussed below.HTTP Request Message Below we provide a typical HTTP request message: GET /somedir/page.html HTTP/1.1 Host: www.someschool.edu Connection: close User-agent: Mozilla/4.0 Accept-language:fr (extra carriage return, line feed)We can learn a lot by taking a good look at this simple request message. First of all, we see that the message is written in ordinary ASCII text, so that your ordinary computer-literate human being can read it. Second, we see that the message consists of five lines, each followed by a carriage return and a line feed. The last line is followed by an additional carriage return and line feed. Although this particular request message has five lines, a request message can have many more lines or as few as one line. The first line of an HTTP request message is called the request line; the subsequent lines are called the header lines. The request line has three fields: the method field, the URL field, and the HTTP version field. The method field can take on several different values, including GET, POST, and HEAD. The great majority of HTTP request messages use the GET method. The GET method is used when the browser requests an object, with the requested object identified in the URL field. In this example, the browser is requesting the object /somedir/page.html. The version is self-explanatory; in this example, the browser implements version HTTP/1.1. Now let's look at the header lines in the example. The header line Host: www. someschool.edu specifies the host on which the object resides. By including the Connection: close header line, the browser is telling the server that it doesn't want to use persistent connections; it wants the server to close the connection after sending the requested object. Although the browser that generated this request message implements HTTP/1.1, it doesn't want to bother with persistent connections. The User-agent: header line specifies the user agent, that is, the browser type that is making the request to the server. Here the user agent is Mozilla/4.0, a Netscape browser. This header line is useful because the server can actually send different versions of the same object to different types of user agents. (Each of the versions is addressed by the same URL.) Finally, the Accept-language: header indicates that the user prefers to receive a French version of the object, if such an object exists on the server; otherwise, the server should send its default version. The Accept-language: header is just one of many content negotiation headers available in HTTP. Having looked at an example, let us now look at the general format for a request message, as shown in Figure 2.7.

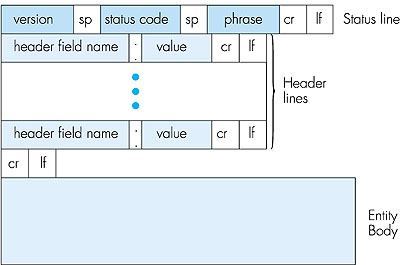

We see that the general format of a request message closely follows our earlier example. You may have noticed, however, that after the header lines (and the additional carriage return and line feed) there is an "entity body." The entity body is not used with the GET method, but is used with the POST method. The HTTP client uses the POST method when the user fills out a form--for example, when a user gives search words to a search engine such as Altavista. With a POST message, the user is still requesting a Web page from the server, but the specific contents of the Web page depend on what the user entered into the form fields. If the value of the method field is POST, then the entity body contains what the user entered into the form fields. The HEAD method is similar to the GET method. When a server receives a request with the HEAD method, it responds with an HTTP message but it leaves out the requested object. The HEAD method is often used by HTTP server developers for debugging. HTTP Response Message Below we provide a typical HTTP response message. This response message could be the response to the example request message just discussed. HTTP/1.1 200 OK Connection: close Date: Thu, 06 Aug 1998 12:00:15 GMT Server: Apache/1.3.0 (Unix) Last-Modified: Mon, 22 Jun 1998 09:23:24 GMT Content-Length: 6821 Content-Type: text/html (data data data data data . . .)Let's take a careful look at this response message. It has three sections: an initial status line, six header lines, and then the entity body. The entity body is the meat of the message--it contains the requested object itself (represented by data data data data data . . .). The status line has three fields: the protocol version field, a status code, and a corresponding status message. In this example, the status line indicates that the server is using HTTP/1.1 and that everything is OK (that is, the server has found, and is sending, the requested object). Now let's look at the header lines. The server uses the Connection: close header line to tell the client that it is going to close the TCP connection after sending the message. The Date: header line indicates the time and date when the HTTP response was created and sent by the server. Note that this is not the time when the object was created or last modified; it is the time when the server retrieves the object from its file system, inserts the object into the response message, and sends the response message. The Server: header line indicates that the message was generated by an Apache Web server; it is analogous to the User-agent: header line in the HTTP request message. The Last-Modified: header line indicates the time and date when the object was created or last modified. The Last-Modified: header, which we will cover in more detail, is critical for object caching, both in the local client and in network cache servers (also known as proxy servers). The Content-Length: header line indicates the number of bytes in the object being sent. The Content-Type: header line indicates that the object in the entity body is HTML text. (The object type is officially indicated by the Content-Type: header and not by the file extension.) Note that if the server receives an HTTP/1.0 request, it will not use persistent connections, even if it is an HTTP/1.1 server. Instead, the HTTP/1.1 server will close the TCP connection after sending the object. This is necessary because an HTTP/1.0 client expects the server to close the connection. Having looked at an example, let us now examine the general format of a response message, which is shown in Figure 2.8. This general format of the response message matches the previous example of a response message.

Let's say a few additional words about status codes and their phrases. The status code and associated phrase indicate the result of the request. Some common status codes and associated phrases include:

telnet www.eurecom.fr 80 GET /~ross/index.html HTTP/1.0(Hit the carriage return twice after typing the second line.) This opens a TCP connection to port 80 of the host www.eurecom.fr and then sends the HTTP GET command. You should see a response message that includes the base HTML file of Professor Ross's homepage. If you'd rather just see the HTTP message lines and not receive the object itself, replace GET with HEAD. Finally, replace /~ross/ index.html with /~ross/banana.html and see what kind of response message you get. In this section we discussed a number of header lines that can be used within HTTP request and response messages. The HTTP specification (especially HTTP/ 1.1) defines many, many more header lines that can be inserted by browsers, Web servers, and network cache servers. We have only covered a small number of the totality of header lines. We will cover a few more below and another small number when we discuss network Web caching at the end of this chapter. A readable and comprehensive discussion of HTTP headers and status codes is given in [Luotonen 1998]. An excellent introduction to the technical issues surrounding the Web is [Yeager 1996]. How does a browser decide which header lines to include in a request message? How does a Web server decide which header lines to include in a response message? A browser will generate header lines as a function of the browser type and version (for example, an HTTP/1.0 browser will not generate any 1.1 header lines), the user configuration of the browser (for example, preferred language), and whether the browser currently has a cached, but possibly out-of-date, version of the object. Web servers behave similarly: There are different products, versions, and configurations, all of which influence which header lines are included in response messages. 2.2.4: User-Server Interaction: Authentication and CookiesWe mentioned above that an HTTP server is stateless. This simplifies server design, and has permitted engineers to develop very high-performing Web servers. However, it is often desirable for a Web site to identify users, either because the server wishes to restrict user access or because it wants to serve content as a function of the user identity. HTTP provides two mechanisms to help a server identify a user: authentication and cookies.Authentication Many sites require users to provide a username and a password in order to access the documents housed on the server. This requirement is referred to as authentication. HTTP provides special status codes and headers to help sites perform authentication. Let's walk through an example to get a feel for how these special status codes and headers work. Suppose a client requests an object from a server, and the server requires user authorization. The client first sends an ordinary request message with no special header lines. The server then responds with empty entity body and with a 401 Authorization Required status code. In this response message the server includes the WWW-Authenticate: header, which specifies the details about how to perform authentication. (Typically, it indicates that the user needs to provide a username and a password.) The client receives the response message and prompts the user for a username and password. The client resends the request message, but this time includes an Authorization: header line, which includes the username and password. After obtaining the first object, the client continues to send the username and password in subsequent requests for objects on the server. (This typically continues until the client closes the browser. However, while the browser remains open, the username and password are cached, so the user is not prompted for a username and password for each object it requests!) In this manner, the site can identify the user for every request. We will see in Chapter 7 that HTTP performs a rather weak form of authentication, one that would not be difficult to break. We will study more secure and robust authentication schemes later in Chapter 7. Cookies Cookies are an alternative mechanism that sites can use to keep track of users. They are defined in RFC 2109. Some Web sites use cookies and others don't. Let's walk through an example. Suppose a client contacts a Web site for the first time, and this site uses cookies. The server's response will include a Set-cookie: header. Often this header line contains an identification number generated by the Web server. For example, the header line might be: Set-cookie: 1678453 When the HTTP client receives the response message, it sees the Set-cookie: header and identification number. It then appends a line to a special cookie file that is stored in the client machine. This line typically includes the host name of the server and user's associated identification number. In subsequent requests to the same server, say one week later, the client includes a Cookie: request header, and this header line specifies the identification number for that server. In the current example, the request message includes the header line: Cookie: 1678453 In this manner, the server does not know the username of the user, but the server does know that this user is the same user that made a specific request one week ago. Web servers use cookies for many different purposes:

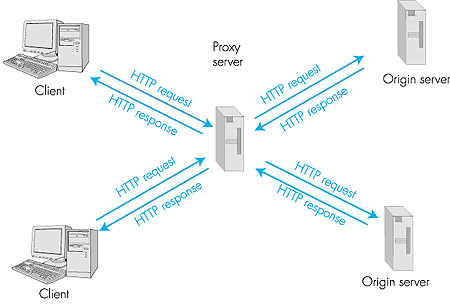

2.2.5: The Conditional GETBy storing previously retrieved objects, Web caching can reduce object-retrieval delays and diminish the amount of Web traffic sent over the Internet. Web caches can reside in a client or in an intermediate network cache server. We will discuss network caching at the end of this chapter. In this subsection, we restrict our attention to client caching.Although Web caching can reduce user-perceived response times, it introduces a new problem--a copy of an object residing in the cache may be stale. In other words, the object housed in the Web server may have been modified since the copy was cached at the client. Fortunately, HTTP has a mechanism that allows the client to employ caching while still ensuring that all objects passed to the browser are up to date. This mechanism is called the conditional GET. An HTTP request message is a so-called conditional GET message if (1) the request message uses the GET method and (2) the request message includes an If-Modified-Since: header line. To illustrate how the conditional get operates, let's walk through an example. First, a browser requests an uncached object from some Web server: GET /fruit/kiwi.gif HTTP/1.0 User-agent: Mozilla/4.0Second, the Web server sends a response message with the object to the client: HTTP/1.0 200 OK Date: Wed, 12 Aug 1998 15:39:29 Server: Apache/1.3.0 (Unix) Last-Modified: Mon, 22 Jun 1998 09:23:24 Content-Type: image/gif (data data data data data ...)The client displays the object to the user but also saves the object in its local cache. Importantly, the client also caches the last-modified date along with the object. Third, one week later, the user requests the same object and the object is still in the cache. Since this object may have been modified at the Web server in the past week, the browser performs an up-to-date check by issuing a conditional get. Specifically, the browser sends GET /fruit/kiwi.gif HTTP/1.0 User-agent: Mozilla/4.0 If-modified-since: Mon, 22 Jun 1998 09:23:24Note that the value of the If-modified-since: header line is exactly equal to the value of the Last-Modified: header line that was sent by the server one week ago. This conditional get is telling the server to send the object only if the object has been modified since the specified date. Suppose the object has not been modified since 22 Jun 1998 09:23:24. Then, fourth, the Web server sends a response message to the client: HTTP/1.0 304 Not Modified Date: Wed, 19 Aug 1998 15:39:29 Server: Apache/1.3.0 (Unix)(empty entity body) We see that in response to the conditional get, the Web server still sends a response message, but does not include the requested object in the response message. Including the requested object would only waste bandwidth and increase user-perceived response time, particularly if the object is large. Note that this last response message has in the status line 304 Not Modified, which tells the client that it can go ahead and use its cached copy of the object. 2.2.6: Web CachesA Web cache--also called a proxy server--is a network entity that satisfies HTTP requests on the behalf of a client. The Web cache has its own disk storage and keeps in this storage copies of recently requested objects. As shown in Figure 2.9, users configure their browsers so that all of their HTTP requests are first directed to the Web cache. (This is a straightforward procedure with Microsoft and Netscape browsers.) Once a browser is configured, each browser request for an object is first directed to the Web cache.

As an example, suppose a browser is requesting the object http://www.someschool.edu/campus.gif.

So why bother with a Web cache? What advantages does it have? Web caches are enjoying wide-scale deployment in the Internet for at least three reasons. First, a Web cache can substantially reduce the response time for a client request, particularly if the bottleneck bandwidth between the client and the origin server is much less than the bottleneck bandwidth between the client and the cache. If there is a high-speed connection between the client and the cache, as there often is, and if the cache has the requested object, then the cache will be able to rapidly deliver the object to the client. Second, as we will soon illustrate with an example, Web caches can substantially reduce traffic on an institution's access link to the Internet. By reducing traffic, the institution (for example, a company or a university) does not have to upgrade bandwidth as quickly, thereby reducing costs. Furthermore, Web caches can substantially reduce Web traffic in the Internet as a whole, thereby improving performance for all applications. In 1998, over 75 percent of Internet traffic was Web traffic, so a significant reduction in Web traffic can translate into a significant improvement in Internet performance [Claffy 1998]. Third, an Internet dense with Web caches--such as, at institutional, regional, and national levels--provides an infrastructure for rapid distribution of content, even for content providers who run their sites on low-speed servers behind low-speed access links. If such a "resource-poor" content provider suddenly has popular content to distribute, this popular content will quickly be copied into the Internet caches, and high user demand will be satisfied. To gain a deeper understanding of the benefits of caches, let us consider an example in the context of Figure 2.10. This figure shows two networks--the institutional network and the rest of the public Internet. The institutional network is a high-speed LAN. A router in the institutional network and a router in the Internet are connected by a 1.5 Mbps link. The origin servers are attached to the Internet, but located all over the globe. Suppose that the average object size is 100 Kbits and that the average request rate from the institution's browsers to the origin servers is 15 requests per second. Also suppose that the amount of time it takes from when the router on the Internet side of the access link in Figure 2.10 forwards an HTTP request (within an IP datagram) until it receives the IP datagram (typically, many IP datagrams) containing the corresponding response is two seconds on average. Informally, we refer to this last delay as the "Internet delay."

The total response time--that is, the time from the browser's request of an object until its receipt of the object--is the sum of the LAN delay, the access delay (that is, the delay between the two routers), and the Internet delay. Let us now do a very crude calculation to estimate this delay. The traffic intensity on the LAN (see Section 1.6) is (15 requests/sec) * (100 Kbits/request)/(10Mbps) = 0.15 whereas the traffic intensity on the access link (from the Internet router to institution router) is (15 requests/sec) * (100 Kbits/request)/(1.5 Mbps) = 1 A traffic intensity of 0.15 on a LAN typically results in, at most, tens of milliseconds of delay; hence, we can neglect the LAN delay. However, as discussed in Section 1.6, as the traffic intensity approaches 1 (as is the case of the access link in Figure 2.10), the delay on a link becomes very large and grows without bound. Thus, the average response time to satisfy requests is going to be on the order of minutes, if not more, which is unacceptable for the institution's users. Clearly something must be done. One possible solution is to increase the access rate from 1.5 Mbps to, say, 10 Mbps. This will lower the traffic intensity on the access link to 0.15, which translates to negligible delays between the two routers. In this case, the total response time will roughly be 2 seconds, that is, the Internet delay. But this solution also means that the institution must upgrade its access link from 1.5 Mbps to 10 Mbps, which can be very costly. Now consider the alternative solution of not upgrading the access link but instead installing a Web cache in the institutional network. This solution is illustrated in Figure 2.11.

Hit rates--the fraction of requests that are satisfied by a cache-- typically range from 0.2 to 0.7 in practice. For illustrative purposes, let us suppose that the cache provides a hit rate of 0.4 for this institution. Because the clients and the cache are connected to the same high-speed LAN, 40 percent of the requests will be satisfied almost immediately, say, within 10 milliseconds, by the cache. Nevertheless, the remaining 60 percent of the requests still need to be satisfied by the origin servers. But with only 60 percent of the requested objects passing through the access link, the traffic intensity on the access link is reduced from 1.0 to 0.6. Typically, a traffic intensity less than 0.8 corresponds to a small delay, say, tens of milliseconds, on a 1.5 Mbps link. This delay is negligible compared with the 2-second Internet delay. Given these considerations, average delay therefore is 0.4 * (0.010 seconds) + 0.6 * (2.01 seconds) which is just slightly greater than 1.2 seconds. Thus, this second solution provides an even lower response time than the first solution, and it doesn't require the institution to upgrade its link to the Internet. The institution does, of course, have to purchase and install a Web cache. But this cost is low--many caches use public-domain software that run on inexpensive servers and PCs. Cooperative Caching Multiple Web caches, located at different places in the Internet, can cooperate and improve overall performance. For example, an institutional cache can be configured to send its HTTP requests to a cache in a backbone ISP at the national level. In this case, when the institutional cache does not have the requested object in its storage, it forwards the HTTP request to the national cache. The national cache then retrieves the object from its own storage or, if the object is not in storage, from the origin server. The national cache then sends the object (within an HTTP response message) to the institutional cache, which in turn forwards the object to the requesting browser. Whenever an object passes through a cache (institutional or national), the cache keeps a copy in its local storage. The advantage of passing through a higher-level cache, such as a national cache, is that it has a larger user population and therefore higher hit rates. An example of a cooperative caching system is the NLANR caching system, which consists of a number of backbone caches in the United States providing ser vice to institutional and regional caches from all over the globe [NLANR 1999]. The NLANR caching hierarchy is shown in Figure 2.12 [Huffaker 1998]. The caches obtain objects from each other using a combination of HTTP and ICP (Internet Caching Protocol). ICP is an application-layer protocol that allows one cache to quickly ask another cache if it has a given document [RFC 2186]; a cache can then use HTTP to retrieve the object from the other cache. ICP is used extensively in many cooperative caching systems and is fully supported by Squid, a popular public-domain software for Web caching [Squid 2000]. If you are interested in learning more about ICP, you are encouraged to see [Luotonen 1998], [Ross 1998], and the ICP RFC [RFC 2186].

An alternative form of cooperative caching involves clusters of caches, often co-located on the same LAN. A single cache is often replaced with a cluster of caches when the single cache is not sufficient to handle the traffic or provide sufficient storage capacity. Although cache clustering is a natural way to scale as traffic increases, clusters introduce a new problem: When a browser wants to request a particular object, to which cache in the cache cluster should it send the request? This problem can be elegantly solved using hash routing. (If you are not familiar with hash functions, you can read about them in Chapter 7.) In the simplest form of hash routing, the browser hashes the URL, and depending on the result of the hash, the browser directs its request message to one of the caches in the cluster. By having all the browsers use the same hash function, an object will never be present in more than one cache in the cluster, and if the object is indeed in the cache cluster, the browser will always direct its request to the correct cache. Hash routing is the essence of the Cache Array Routing Protocol (CARP). Additional information is available if you are interested in learning more about hash routing or CARP [Valloppillil 1997; Luotonen 1998; Ross 1997, 1998]. Web caching is a rich and complex subject. Web caching has also enjoyed extensive research and product development in recent years. Furthermore, caches are now being built to handle streaming audio and video. Caches will likely play an important role as the Internet begins to provide an infrastructure for the large-scale, on-demand distribution of music, television shows, and movies in the Internet. |