2.3: File Transfer: FTP

| FTP (File Transfer

Protocol) is a protocol for transferring a file from one host to another

host. The protocol dates back to 1971 (when the Internet was still an experiment),

but remains enormously popular. FTP is described in RFC 959. Figure 2.13

provides an overview of the services provided by FTP.

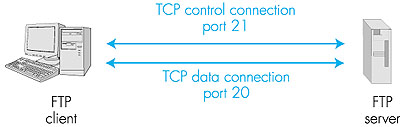

In a typical FTP session, the user is sitting in front of one host (the local host) and wants to transfer files to or from a remote host. In order for the user to access the remote account, the user must provide a user identification and a password. After providing this authorization information, the user can transfer files from the local file system to the remote file system and vice versa. As shown in Figure 2.13, the user interacts with FTP through an FTP user agent. The user first provides the hostname of the remote host, causing the FTP client process in the local host to establish a TCP connection with the FTP server process in the remote host. The user then provides the user identification and password, which get sent over the TCP connection as part of FTP commands. Once the server has authorized the user, the user copies one or more files stored in the local file system into the remote file system (or vice versa). HTTP and FTP are both file transfer protocols and have many common characteristics; for example, they both run on top of TCP. However, the two application-layer protocols have some important differences. The most striking difference is that FTP uses two parallel TCP connections to transfer a file, a control connection and a data connection. The control connection is used for sending control information between the two hosts--information such as user identification, password, commands to change remote directory, and commands to "put" and "get" files. The data connection is used to actually send a file. Because FTP uses a separate control connection, FTP is said to send its control information out-of-band. In Chapter 6 we shall see that the RTSP protocol, which is used for controlling the transfer of continuous media such as audio and video, also sends its control information out-of-band. HTTP, as you recall, sends request and response header lines into the same TCP connection that carries the transferred file itself. For this reason, HTTP is said to send its control information in-band. In the next section we shall see that SMTP, the main protocol for electronic mail, also sends control information in-band. The FTP control and data connections are illustrated in Figure 2.14.

When a user starts an FTP session with a remote host, FTP first sets up a control TCP connection on server port number 21. The client side of FTP sends the user identification and password over this control connection. The client side of FTP also sends, over the control connection, commands to change the remote directory. When the user requests a file transfer (either to, or from, the remote host), FTP opens a TCP data connection on server port number 20. FTP sends exactly one file over the data connection and then closes the data connection. If, during the same session, the user wants to transfer another file, FTP opens another data connection. Thus, with FTP, the control connection remains open throughout the duration of the user session, but a new data connection is created for each file transferred within a session (that is, the data connections are nonpersistent). Throughout a session, the FTP server must maintain state about the user. In particular, the server must associate the control connection with a specific user account, and the server must keep track of the user's current directory as the user wanders about the remote directory tree. Keeping track of this state information for each ongoing user session significantly constrains the total number of sessions that FTP can maintain simultaneously. HTTP, on the other hand, is stateless--it does not have to keep track of any user state. 2.3.1: FTP Commands and RepliesWe end this section with a brief discussion of some of the more common FTP commands. The commands, from client to server, and replies, from server to client, are sent across the control connection in seven-bit ASCII format. Thus, like HTTP commands, FTP commands are readable by people. In order to delineate successive commands, a carriage return and line feed end each command (and reply). Each command consists of four uppercase ASCII characters, some with optional arguments. Some of the more common commands are given below (with options in italics):

|