4.2: Routing Principles

| In order to

transfer packets from a sending host to the destination host, the network

layer must determine the path or route that the packets are

to follow. Whether the network layer provides a datagram service (in which

case different packets between a given host-destination pair may take different

routes) or a virtual-circuit service (in which case all packets between

a given source and destination will take the same path), the network layer

must nonetheless determine the path for a packet. This is the job of the

network layer routing protocol.

At the heart of any routing protocol is the algorithm (the routing algorithm) that determines the path for a packet. The purpose of a routing algorithm is simple: given a set of routers, with links connecting the routers, a routing algorithm finds a "good" path from source to destination. Typically, a "good" path is one that has "least cost." We'll see, however, that in practice, real-world concerns such as policy issues (for example, a rule such as "router X, belonging to organization Y should not forward any packets originating from the network owned by organization Z") also come into play to complicate the conceptually simple and elegant algorithms whose theory underlies the practice of routing in today's networks. The graph abstraction used to formulate routing algorithms is shown in Figure 4.4. To view some graphs representing real network maps, see [Dodge 1999]; for a discussion of how well different graph-based models model the Internet, see [Zegura 1997]. Here, nodes in the graph represent routers--the points at which packet routing decisions are made--and the lines ("edges" in graph theory terminology) connecting these nodes represent the physical links between these routers. A link also has a value representing the "cost" of sending a packet across the link. The cost may reflect the level of congestion on that link (for example, the current average delay for a packet across that link) or the physical distance traversed by that link (for example, a transoceanic link might have a higher cost than a short-haul terrestrial link). For our current purposes, we'll simply take the link costs as a given and won't worry about how they are determined.

Given the graph abstraction, the problem of finding the least-cost path from a source to a destination requires identifying a series of links such that:

As a simple exercise, try finding the least-cost path from nodes A to F, and reflect for a moment on how you calculated that path. If you are like most people, you found the path from A to F by examining Figure 4.4, tracing a few routes from A to F, and somehow convincing yourself that the path you had chosen had the least cost among all possible paths. (Did you check all of the 12 possible paths between A and F? Probably not!) Such a calculation is an example of a centralized routing algorithm--the routing algorithm was run in one location, your brain, with complete information about the network. Broadly, one way in which we can classify routing algorithms is according to whether they are global or decentralized:

Only two types of routing algorithms are typically used in the Internet: a dynamic global link state algorithm, and a dynamic decentralized distance vector algorithm. We cover these algorithms in Section 4.2.1 and 4.2.2, respectively. Other routing algorithms are surveyed briefly in Section 4.2.3. 4.2.1: A Link State Routing AlgorithmRecall that in a link state algorithm, the network topology and all link costs are known; that is, available as input to the link state algorithm. In practice this is accomplished by having each node broadcast the identities and costs of its attached links to all other routers in the network. This link state broadcast [Perlman 1999], can be accomplished without the nodes having to initially know the identities of all other nodes in the network. A node need only know the identities and costs to its directly attached neighbors; it will then learn about the topology of the rest of the network by receiving link state broadcasts from other nodes. (In Chapter 5, we will learn how a router learns the identities of its directly attached neighbors). The result of the nodes' link state broadcast is that all nodes have an identical and complete view of the network. Each node can then run the link state algorithm and compute the same set of least-cost paths as every other node.The link state algorithm we present below is known as Dijkstra's algorithm, named after its inventor. A closely related algorithm is Prim's algorithm; see [Corman 1990] for a general discussion of graph algorithms. Dijkstra's algorithm computes the least-cost path from one node (the source, which we will refer to as A) to all other nodes in the network. Dijkstra's algorithm is iterative and has the property that after the kth iteration of the algorithm, the least-cost paths are known to k destination nodes, and among the least-cost paths to all destination nodes, these k paths will have the k smallest costs. Let us define the following notation:

Link State (LS) Algorithm: 1 Initialization:

2 N = {A}

3 for all nodes v

4 if v adjacent to A

5 then D(v) = c(A,v)

6 else D(v) =

As an example,

let's consider the network in Figure 4.4 and compute the least-cost paths

from A to all possible destinations. A tabular summary of the algorithm's

computation is shown in Table 4.2, where each line in the table gives the

values of the algorithm's variables at the end of the iteration.

Table 4.2: Running the link state algorithm on the network in Figure 4.4

Let's consider the few first steps in detail:

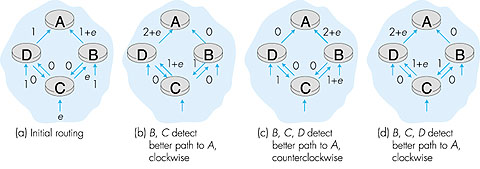

What is the computational complexity of this algorithm? That is, given n nodes (not counting the source), how much computation must be done in the worst case to find the least-cost paths from the source to all destinations? In the first iteration, we need to search through all n nodes to determine the node, w, not in N that has the minimum cost. In the second iteration, we need to check n - 1 nodes to determine the minimum cost; in the third iteration n - 2 nodes, and so on. Overall, the total number of nodes we need to search through over all the iterations is n(n + 1)/2, and thus we say that the above implementation of the link state algorithm has worst-case complexity of order n squared: O(n2). (A more sophisticated implementation of this algorithm, using a data structure known as a heap, can find the minimum in line 9 in logarithmic rather than linear time, thus reducing the complexity.) Before completing our discussion of the LS algorithm, let us consider a pathology that can arise. Figure 4.5 shows a simple network topology where link costs are equal to the load carried on the link, for example, reflecting the delay that would be experienced. In this example, link costs are not symmetric, that is, c(A,B) equals c(B,A) only if the load carried on both directions on the AB link is the same. In this example, node D originates a unit of traffic destined for A, node B also originates a unit of traffic destined for A, and node C injects an amount of traffic equal to e, also destined for A. The initial routing is shown in Figure 4.5(a) with the link costs corresponding to the amount of traffic carried.

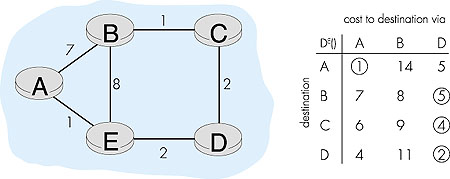

When the LS algorithm is next run, node C determines (based on the link costs shown in Figure 4.5a) that the clockwise path to A has a cost of 1, while the counterclockwise path to A (which it had been using) has a cost of 1 + e. Hence C's least-cost path to A is now clockwise. Similarly, B determines that its new least-cost path to A is also clockwise, resulting in costs shown in Figure 4.5b. When the LS algorithm is run next, nodes B, C, and D all detect a zero-cost path to A in the counterclockwise direction, and all route their traffic to the counterclockwise routes. The next time the LS algorithm is run, B, C, and D all then route their traffic to the clockwise routes. What can be done to prevent such oscillations (which can occur in any algorithm that uses a congestion or delay-based link metric). One solution would be to mandate that link costs not depend on the amount of traffic carried--an unacceptable solution since one goal of routing is to avoid highly congested (for example, high-delay) links. Another solution is to ensure that all routers do not run the LS algorithm at the same time. This seems a more reasonable solution, since we would hope that even if routers run the LS algorithm with the same periodicity, the execution instance of the algorithm would not be the same at each node. Interestingly, researchers have recently noted that routers in the Internet can self-synchronize among themselves [Floyd Synchronization 1994]. That is, even though they initially execute the algorithm with the same period but at different instants of time, the algorithm execution instance can eventually become, and remain, synchronized at the routers. One way to avoid such self-synchronization is to purposefully introduce randomization into the period between execution instants of the algorithm at each node. Having now studied the link state algorithm, let's next consider the other major routing algorithm that is used in practice today--the distance vector routing algorithm. 4.2.2: A Distance Vector Routing AlgorithmWhile the LS algorithm is an algorithm using global information, the distance vector (DV) algorithm is iterative, asynchronous, and distributed. It is distributed in that each node receives some information from one or more of its directly attached neighbors, performs a calculation, and may then distribute the results of its calculation back to its neighbors. It is iterative in that this process continues on until no more information is exchanged between neighbors. (Interestingly, we will see that the algorithm is self terminating--there is no "signal" that the computation should stop; it just stops.) The algorithm is asynchronous in that it does not require all of the nodes to operate in lock step with each other. We'll see that an asynchronous, iterative, self terminating, distributed algorithm is much more interesting and fun than a centralized algorithm!The principal data structure in the DV algorithm is the distance table maintained at each node. Each node's distance table has a row for each destination in the network and a column for each of its directly attached neighbors. Consider a node X that is interested in routing to destination Y via its directly attached neighbor Z. Node X's distance table entry, Dx(Y,Z) is the sum of the cost of the direct one-hop link between X and Z, c(X,Z), plus neighbor Z's currently known minimum-cost path from itself (Z) to Y. That is: Dx(Y,Z) = c(X,Z) + minw{Dz(Y,w)} The minw term in the equation is taken over all of Z's directly attached neighbors (including X, as we shall soon see). The equation suggests the form of the neighbor-to-neighbor communication that will take place in the DV algorithm--each node must know the cost of each of its neighbors' minimum-cost path to each destination. Thus, whenever a node computes a new minimum cost to some destination, it must inform its neighbors of this new minimum cost. Before presenting the DV algorithm, let's consider an example that will help clarify the meaning of entries in the distance table. Consider the network topology and the distance table shown for node E in Figure 4.6. This is the distance table in node E once the DV algorithm has converged. Let's first look at the row for destination A.

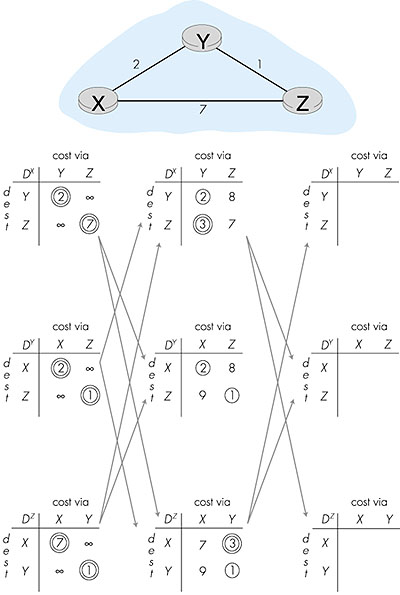

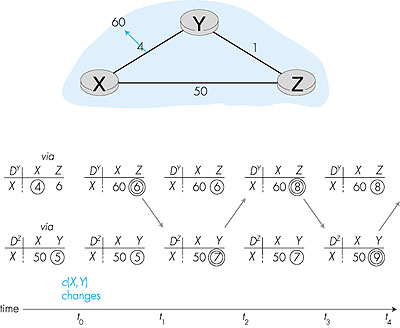

In discussing the distance table entries for node E above, we informally took a global view, knowing the costs of all links in the network. The distance vector algorithm we will now present is decentralized and does not use such global information. Indeed, the only information a node will have are the costs of the links to its directly attached neighbors, and information it receives from these directly attached neighbors. The distance vector algorithm we will study is also known as the Bellman-Ford algorithm, after its inventors. It is used in many routing protocols in practice, including: Internet BGP, ISO IDRP, Novell IPX, and the original ARPAnet. Distance Vector (DV) algorithm At each node, X: 1 Initialization: 2 for all adjacent nodes v: 3 DX (*,v) =The key steps are lines 15 and 21, where a node updates its distance table entries in response to either a change of cost of an attached link or the receipt of an update message from a neighbor. The other key step is line 24, where a node sends an update to its neighbors if its minimum cost path to a destination has changed. Figure 4.7 illustrates the operation of the DV algorithm for the simple three node network shown at the top of the figure. The operation of the algorithm is illustrated in a synchronous manner, where all nodes simultaneously receive messages from their neighbors, compute new distance table entries, and inform their neighbors of any changes in their new least path costs. After studying this example, you should convince yourself that the algorithm operates correctly in an asynchronous manner as well, with node computations and update generation/reception occurring at any times.

The circled distance table entries in Figure 4.7 show the current minimum path cost to a destination. A double-circled entry indicates that a new minimum cost has been computed (in either line 4 of the DV algorithm (initialization) or line 21). In such cases an update message will be sent (line 24 of the DV algorithm) to the node's neighbors as represented by the arrows between columns in Figure 4.7. The leftmost column in Figure 4.7 shows the distance table entries for nodes X, Y, and Z after the initialization step. Let's now consider how node X computes the distance table shown in the middle column of Figure 4.7 after receiving updates from nodes Y and Z. As a result of receiving the updates from Y and Z, X computes in line 21 of the DV algorithm:

It is important to note that the only reason that X knows about the terms minw DZ(Y,w) and minw DY(Z,w) is because nodes Z and Y have sent those values to X (and are received by X in line 10 of the DV algorithm). As an exercise, verify the distance tables computed by Y and Z in the middle column of Figure 4.7. The value DX(Z,Y) = 3 means that X's minimum cost to Z has changed from 7 to 3. Hence, X sends updates to Y and Z informing them of this new least cost to Z. Note that X need not update Y and Z about its cost to Y since this has not changed. Note also that although Y's recomputation of its distance table in the middle column of Figure 4.7 does result in new distance entries, it does not result in a change of Y's least-cost path to nodes X and Z. Hence Y does not send updates to X and Z. The process of receiving updated costs from neighbors, recomputation of distance table entries, and updating neighbors of changed costs of the least-cost path to a destination continues until no update messages are sent. At this point, since no update messages are sent, no further distance table calculations will occur and the algorithm enters a quiescent state; that is, all nodes are performing the wait in line 9 of the DV algorithm. The algorithm would remain in the quiescent state until a link cost changes, as discussed below. The Distance Vector Algorithm: Link Cost Changes and Link Failure When a node running the DV algorithm detects a change in the link cost from itself to a neighbor (line 12), it updates its distance table (line 15) and, if there's a change in the cost of the least-cost path, updates its neighbors (lines 23 and 24). Figure 4.8 illustrates this behavior for a scenario where the link cost from Y to X changes from 4 to 1. We focus here only on Y and Z's distance table entries to destination (row) X.

Let's now consider what can happen when a link cost increases. Suppose that the link cost between X and Y increases from 4 to 60 as shown in Figure 4.9.

Distance Vector Algorithm: Adding Poisoned Revers The specific looping scenario illustrated in Figure 4.9 can be avoided using a technique known as poisoned reverse. The idea is simple--if Z routes through Y to get to destination X, then Z will advertise to Y that its (Z's) distance to X is infinity. Z will continue telling this little "white lie" to Y as long as it routes to X via Y. Since Y believes that Z has no path to X, Y will never attempt to route to X via Z, as long as Z continues to route to X via Y (and lies about doing so). Figure 4.10 illustrates how poisoned reverse solves the particular looping problem we encountered before in Figure 4.9. As a result of the poisoned reverse, Y's distance table indicates an infinite cost when routing to X via Z (the result of Z having informed Y that Z's cost to X was infinity). When the cost of the XY link changes from 4 to 60 at time t0, Y updates its table and continues to route directly to X, albeit at a higher cost of 60, and informs Z of this change in cost. After receiving the update at t1, Z immediately shifts its route to X to be via the direct ZX link at a cost of 50. Since this is a new least-cost to X, and since the path no longer passes through Y, Z informs Y of this new least-cost path to X at t2. After receiving the update from Z, Y updates its distance table to route to X via Z at a least cost of 51. Also, since Z is now on Y's least-cost path to X, Y poisons the reverse path from Z to X by informing Z at time t3 that it (Y) has an infinite cost to get to X. The algorithm becomes quiescent after t4, with distance table entries for destination X shown in the rightmost column in Figure 4.10.

Does poison reverse solve the general count-to-infinity problem? It does not. You should convince yourself that loops involving three or more nodes (rather than simply two immediately neighboring nodes, as we saw in Figure 4.10) will not be detected by the poison reverse technique. A Comparison of Link State and Distance Vector Routing Algorithms Let's conclude our study of link state and distance vector algorithms with a quick comparison of some of their attributes.

4.2.3: Other Routing AlgorithmsThe LS and DV algorithms we have studied are not only widely used in practice, they are essentially the only routing algorithms used in practice today.Nonetheless, many routing algorithms have been proposed by researchers over the past 30 years, ranging from the extremely simple to the very sophisticated and complex. One of the simplest routing algorithms proposed is hot potato routing. The algorithm derives its name from its behavior--a router tries to get rid of (forward) an outgoing packet as soon as it can. It does so by forwarding it on any outgoing link that is not congested, regardless of destination. Another broad

class of routing algorithms are based on viewing packet traffic as flows

between sources and destinations in a network. In this approach, the routing

problem can be formulated mathematically as a constrained optimization

problem known as a network flow problem [Bertsekas

1991]. Let us define

ijm as the amount of source i, destination

j traffic passing through link m. The optimization problem

then is to find the set of link flows, {

ijm as the amount of source i, destination

j traffic passing through link m. The optimization problem

then is to find the set of link flows, { ijm}

for all links m and all sources, i, and destinations, j,

that satisfies the constraints above and optimizes a performance measure

that is a function of { ijm}

for all links m and all sources, i, and destinations, j,

that satisfies the constraints above and optimizes a performance measure

that is a function of { ijm}.

The solution to this optimization problem then defines the routing used

in the network. For example, if the solution to the optimization problem

is such that ijm}.

The solution to this optimization problem then defines the routing used

in the network. For example, if the solution to the optimization problem

is such that  ijm

= ijm

=  ij for some

link m, then all i-to-j traffic will be routed over

link m. In particular, if link m is attached to node i,

then m is the first hop on the optimal path from source i

to destination j. ij for some

link m, then all i-to-j traffic will be routed over

link m. In particular, if link m is attached to node i,

then m is the first hop on the optimal path from source i

to destination j.

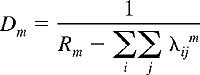

But what performance function should be optimized? There are many possible choices. If we make certain assumptions about the size of packets and the manner in which packets arrive at the various routers, we can use the so-called M/M/1 queuing theory formula [Kleinrock 1975] to express the average delay at link m as:

where Rm

is link m's capacity (measured in terms of the average number of

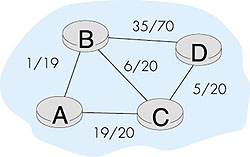

packets/sec it can transmit) and The final set of routing algorithms we mention here are those derived from the telephony world. These circuit-switched routing algorithms are of interest to packet-switched data networking in cases where per-link resources (for example, buffers, or a fraction of the link bandwidth) are to be reserved for each connection that is routed over the link. While the formulation of the routing problem might appear quite different from the least-cost routing formulation we have seen in this chapter, we will see that there are a number of similarities, at least as far as the path finding algorithm (routing algorithm) is concerned. Our goal here is to provide a brief introduction for this class of routing algorithms. The reader is referred to [Ash 1998; Ross 1995; Girard 1990] for a detailed discussion of this active research area. The circuit-switched routing problem formulation is illustrated in Figure 4.11. Each link has a certain amount of resources (for example, bandwidth). The easiest (and a quite accurate) way to visualize this is to consider the link to be a bundle of circuits, with each call that is routed over the link requiring the dedicated use of one of the link's circuits. A link is thus characterized both by its total number of circuits, as well as the number of these circuits currently in use. In Figure 4.11, all links except AB and BD have 20 circuits; the number to the left of the number of circuits indicates the number of circuits currently in use.

Suppose now that a call arrives at node A, destined to node D. What path should be taken? In shortest path first (SPF) routing, the shortest path (least number of links traversed) is taken. We have already seen how the Dijkstra LS algorithm can be used to find shortest-path routes. In Figure 4.11, either the ABD or ACD path would thus be taken. In least loaded path (LLP) routing, the load at a link is defined as the ratio of the number of used circuits at the link and the total number of circuits at that link. The path load is the maximum of the loads of all links in the path. In LLP routing, the path taken is that with the smallest path load. In Figure 4.11, the LLP path is ABCD. In maximum free circuit (MFC) routing, the number of free circuits associated with a path is the minimum of the number of free circuits at each of the links on a path. In MFC routing, the path with the maximum number of free circuits is taken. In Figure 4.11, the path ABD would be taken with MFC routing. Given these examples from the circuit-switching world, we see that the path selection algorithms have much the same flavor as LS routing. All nodes have complete information about the network's link states. Note, however, that the potential consequences of old or inaccurate state information are more severe with circuit-oriented routing--a call may be routed along a path only to find that the circuits it had been expecting to be allocated are no longer available. In such a case, the call setup is blocked and another path must be attempted. Nonetheless, the main differences between connection-oriented, circuit-switched routing and connectionless packet-switched routing come not in the path-selection mechanism, but rather in the actions that must be taken when a connection is set up, or torn down, from source to destination. |

.

We will assume for simplicity that c(i,j) equals c(j,i).

.

We will assume for simplicity that c(i,j) equals c(j,i).

i

i