8.2: The Infrastructure for Network Management

| We've seen

in the previous section that network management requires the ability to

"monitor, test, poll, configure, . . . and control" the hardware and software

and components in a network. Because the network devices are distributed,

this will minimally require that the network administrator be able to gather

data (for example, for monitoring purposes) from a remote entity and be

able to affect changes (for example, control) at that remote entity. A

human analogy will prove useful here for understanding the infrastructure

needed for network management.

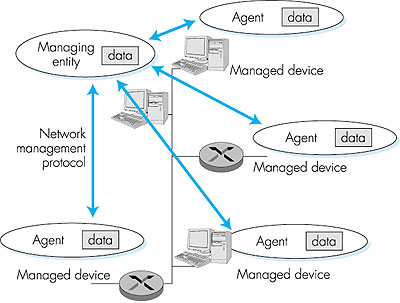

Imagine that you're the head of a large organization that has branch offices around the world. It's your job to make sure that the pieces of your organization are operating smoothly. How would you do so? At a minimum, you'll periodically gather data from your branch offices in the form of reports and various quantitative measures of activity, productivity, and budget. You'll occasionally (but not always) be explicitly notified when there's a problem in one of the branch offices; the branch manager who wants to climb the corporate ladder (perhaps to get your job) may send you unsolicited reports indicating how smoothly things are running at his/her branch. You'll sift through the reports you receive, hoping to find smooth operations everywhere, but no doubt finding problems in need of your attention. You might initiate a one-on-one dialogue with one of your problem branch offices, gather more data in order to understand the problem, and then pass down an executive order ("Make this change!") to the branch office manager. Implicit in this very common human scenario is an infrastructure for controlling the organization--the boss (you), the remote sites being controlled (the branch offices), your remote agents (the branch office managers), communication protocols (for transmitting standard reports and data, and for one-on-one dialogues), and data (the report contents and the quantitative measures of activity, productivity, and budget). Each of these components in human organizational management has a counterpart in network management. The architecture of a network management system is conceptually identical to this simple human organizational analogy. The network management field has its own specific terminology for the various components of a network management architecture, and so we adopt that terminology here. As shown in Figure 8.2, there are three principle components of a network management architecture: a managing entity (the boss in our above analogy--you), the managed devices (the branch office), and a network management protocol.

The managing entity is an application, typically with a human in the loop, running in a centralized network management station in the network operations center (NOC). The managing entity is the locus of activity for network management; it controls the collection, processing, analysis, and/or display of network management information. It is here that actions are initiated to control network behavior and here that the human network administrator interacts with the network devices. A managed device is a piece of network equipment (including its software) that resides on a managed network. This is the branch office in our human analogy. A managed device might be a host, router, bridge, hub, printer, or modem device. Within a managed device, there may be several so-called managed objects. These managed objects are the actual pieces of hardware within the managed device (for example, a network interface card), and the sets of configuration parameters for the pieces of hardware and software (for example, an intradomain routing protocol such as RIP). In our human analogy, the managed objects might be the departments within the branch office. These managed objects have pieces of information associated with them that are collected into a management information base (MIB); we'll see that the values of these pieces of information are available to (and in many cases able to be set by) the managing entity. In our human analogy, the MIB corresponds to quantitative data (measures of activity, productivity, and budget, with the latter being setable by the managing entity!) exchanged between the branch office and the main office. We'll study MIBs in detail in Section 8.3. Finally, also resident in each managed device is a network management agent, a process running in the managed device that communicates with the managing entity, taking local actions on the managed device under the command and control of the managing entity. The network management agent is the branch manager in our human analogy. The third piece of a network management architecture is the network management protocol. The protocol runs between the managing entity and the managed devices, allowing the managing entity to query the status of managed devices and indirectly take actions at these devices via its agents. Agents can use the network management protocol to inform the managing entity of exceptional events (for example, component failures or violation of performance thresholds). It's important to note that the network management protocol does not itself manage the network. Instead, it provides a tool with which the network administrator can manage ("monitor, test, poll, configure, analyze, evaluate and control") the network. This is a subtle, but important distinction. Although the infrastructure for network management is conceptually simple, one can often get bogged down with the network-management-speak vocabulary of "managing entity," "managed device," "managing agent," and "management information base." For example, in network-management-speak, our simple host monitoring scenario, "managing agents" located at "managed devices" are periodically queried by the "managing entity"--a simple idea, but a linguistic mouthful! Hopefully, keeping the human organizational analogy and its obvious parallels with network management in mind will be of help as we continue through this chapter. Our discussion of network management architecture above has been generic, and broadly applies to a number of the network-management standards and efforts that have been proposed over the years. Network-management standards began maturing in the late 1980s, with OSI CMISE/CMIP (the Common Management Service Element/Common Management Information Protocol) [Piscatello 1993; Stallings 1993; Glitho 1998] and the Internet SNMP (Simple Network-Management Protocol) [Stallings 1993; RFC 2570, Stallings 1999; Rose 1996] emerging as the two most important standards [Miller 1997; Subramanian 2000]. Both are designed to be independent of vendor-specific products or networks. Because SNMP was quickly designed and deployed at a time when the need for network management was becoming painfully clear, SNMP found widespread use and acceptance. Today, SNMP has emerged as the most widely used and deployed network management framework. We cover SNMP in detail in the following section. |